|

Stèles juives à Dijon

"An Uncertain Future" de Robert I. Weiner & Richard E. Sharpless (en Anglais: Voix de la communauté juive de Dijon 1940-2012)

Article sur la Synagogue par Michel Levy

|

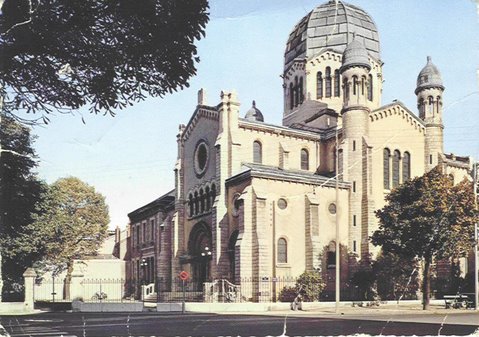

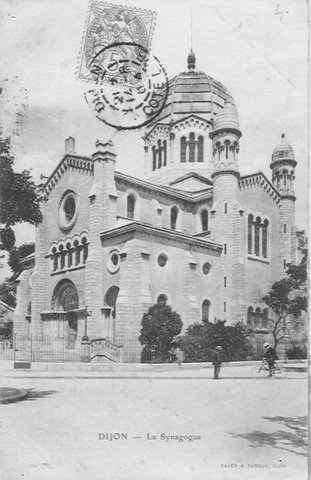

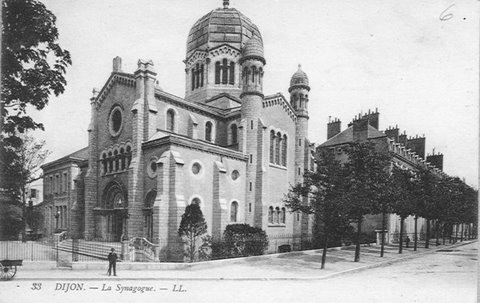

HISTOIRE La Communauté compte aujourd’hui 240 familles, originaires en grande partie du Maghreb, mais également de la région

d’Alsace et d’Europe de l’Est. Elle s’est constituée en 1835. Une Synagogue fut construite en 1870. Le Centre Communautaire

a été inauguré en 1980. Commerçants, employés, fonctionnaires et professions libérales constituent la majorité de la population

juive. Les offices sont célébrés selon le rite sépharade. Aux Archives municipales et départementales, on peut consulter plusieurs

brochures concernant cette communauté depuis le XIIIème siècle. Une très importante collection de pierres tombales juives

se trouve dans les caves du Musée Archéologique. Il existe aussi de très nombreux documents concernant l’époque des Ducs de

Bourgogne et la période de 1795-1905. LE CENTENAIRE

DE LA SYNAGOGUE DE DIJON

Restauration des vitraux par M. Simon Buri - Architecte

Cliquer sur le lien ci-dessus pour connaître l'historique de la Synagogue de Dijon du point de vue de son

architecture. Le texte est celui de l'allocution de Monsieur Simon Buri, Architecte, qui a mené à

terme la réfection des vitraux qui ont été inaugurés lors d'une cérémonie le jeudi

3 novembre 2011

|

Pour en savoir plus, lire l'histoire des Juifs bourguignons de Henri-Claude

Bloch (z.l.) Ci-contre et ci-dessous, collection privée de cartes

postales de la Synagogue de Dijon mise à disposition par Henri-Claude Bloch, ancien Président de la Communauté

décédé en 2008.

HISTOIRE D'UN HISTORIEN DIJONNAIS - ROBERT SCHNERB (Parent de la famille de Claude Israël)

Cliquer le lien ci-dessus

|

|

Jewish tombstones according

to Rabbi Gerson In a big number of cities Jews grouped in order to form

communities. They were so numerous in Baigneux that the city was given the name of Baigneux-les-Juifs (they were expelled

from the city by Jean le Grand under the orders of the duke Philippe in 1420.) Dijon, Châtillon, Beaune, Nuit, Arnay-le-Duc, Saulieu, etc, had jewish quarters

or streets of the Jews. Jews had many difficulties in order to possess a piece of land dedicated to the shrouding of

the dead. The law allowing the establishment of a Jewish cemetery was carefully recorded in the public acts (in Dijon,

the cemetery was on Grand-Potet street (rue Buffon); in 1250, it must have been quite extended since skeletons were discovered

into Buffon street and many gravestones, whole or broken, were discovered in square Rameau. After the expulsion of the Jews

of France in 1306, we can still find Jews in Burgundy but their cemetery is no longer tolerated near the city of Dijon: it

is transferred 12 km from the city to a locality called “Les Baraques de Gevrey” on the route to Beaune, a hundred

paces in the east of the big way (Chemin) (called Courtépée); there is no jew who does not go in his way to

pray on the tombs. Under the reign

of Philippe le Hardi, a cemetery was anew authorised in 1373 close to the city at the cost of “a golden franc”

per head, and this continued until 1395 date of the final expulsion.

The Jewish tombstones which were discovered in 1885-1900 come from different Jewish cemeteries of the city. They have no date

and were mostly discovered and mistaken for quarry-stone from Castrum. Some stones were discovered in Vauban street in

the cellars of the old hospital of Saint Fiacre and could be dated to the first centuries of the monarchy (discovered in walls

of that era): some were admirably well preserved (in the Archeological museum). Here are some inscriptions which were

picked up and published in the archives of the scientific missions: Siona, daughter of Rabbi Samuel

Esther, daughter of Saint Isaac Isaac, son of Aron

Simpha, daughter of Aron Bethasbee, daughter of Jacob

R. Simon, son of Menachem Hiskya B.R. Mordechai

Hanna, daughter of R. Isaac Ivette, daughter of R. Isaac

Léa, daughter of R. Isaac R.Levy B. Isaac Mordechai B.R. Tobia Nappecha, daughter of R. Reahabia As you may have noticed many rabbis are cited; it is not impossible that these rabbis

may have been known in the Jewish literature of the Middle Ages. Regular accounts must have existed among the heads of synagogues

in Burgundy and those of Troyes and Ranrupt.

The prayer ritual and religious poetry known under the name of “Siddour of Rachi or Mahzor of Vitry” was beyond

doubt widely known in the numerous communities of the old duchy of Burgundy, but they also had a Siddour of the liturgy in

Burgundy. As a result the Rabbis of Burgundy in establishing a special liturgy for the use of their own communities,

must have enjoyed a certain undisputable spiritual authority.

The “Rabbi of Dijon” seems to have lived towards 1250 and is probably the one cited under the name

Rabby in the manuscript registry of the Jewish possessions after their expulsion in 1306. Rabbi, Simha Hazzan towards

1260, the anonymous author of our “Mazzor of Bourgogne”, may have been the same person. At the same period

we can find: Rabbi Eliezer Ben Yehouda who sets down the Mahzor that his

master Menahem B. Joseph had composed in Champagne. Rabbi Eliazar originated from Burgundy and Rabbi Joseph B. Meir of Saulieu

was without doubt the son of Rabbi Meir of Dijon.

A precious manuscript composed of 24 books (24 canonical books of the old testament) was invented in 1306 and then resold

(according to Simonet) to the Jews for 25 pounds of gold. As a reminder, a manuscript scroll of the Pentateuch going back

to a high antiquity was kept in Burgundy, a scroll that Maimonides may have consulted ?

Translation by Luna Cemachovic

|

Expulsion of the Jews of Burgundy.

An inventory of their property According abbot Mariller and Clement. Janin. Jews appear in the Duchy of Burgundy, according to the texts

only at the end of the Xe century. It is true that the Gombette decree

accords them an article stating a high pecuniary penalty in order to buy back injuries inflicted to Christians, if they want

to avoid having their hand cut. It is also true , that two canon laws of the

Mâcon Council held in 581, fixes at 12 francs, the selling price for their

Christian slaves, and they forbid them any job such as magistrate or tax-collector. Jews were excluded from

franchises and privileges (Charte of Seurre, February 1245). “Jews were serfs, that

is entirely at someone’s beck and call. Their lord could demand from them any price for a tax he wanted , therefore

the lord was the one to profit from the Jews’ usury while, for the population, Jews were the ones responsible for odious

behaviour”.

Jews, which were the lord’s or each duke’s property, were paying an annual quit-rent more or less elevated,

such as of one golden marc imposed on the Jew Dieudonné, of Bar, from the son of Hugues from Burgundy in 1250.

The city of Chatillon –Sur-Seine was an important Jewish

centre; we know this from a chart in 1273 by the duke Robert who gives to his

mother-in-law as part of a jointure the manor, the guardianship of the abbey and the Jews of Chatillon. The Jewish communities of Dijon, Châtillon,

Chalon, Auxonne, Buxy, Semur, Saulieu, Avallon, and Montbard flourished. Rabbis,

famous writers, according to competent authors of Hebraic literature, came from Dijon, Saulieu, Nuit, Avallon, and Pierre. Dijon had 22 houses, a synagogue and its annexes, a cemetery, and an assembly hall

for Shabbat. Of an incredible activity, this small population which hardly represents

a hundred families, lends, sells and has commercial exchanges with the big and the humble, more often with the latter ones,

as pawnbrokers, from a humble woman’s corset to a lord’s castle. When

the Duke Robert dictated his will, he specified in 1302: “I saw that, without better judgement, the Jews stay in my

territory mainly for humanity, and they trade without usury, and live of their labour, and that from now on they do not have

to pay to those who hate usury.” The dominant idea in those last wishes of Robert the II is the reconciliation between Jews and Christians

rather than the bitter will to rob each other, a dominant feature in the French legislation by the time of Philippe Le Bel. In 1305, the Royal Treasury needed money so badly

that in order to procure immediately considerable sums of money, Philippe Le Bel decides to lose in the future the permanent

albeit variable income from the Jews: he banishes them all and violently takes hold of their belongings, furniture and houses.

The repercussion of this measure did not take long from coming in Burgundy and in 1306, all the Jews of the duchy were arrested. In Dijon, the three commissaries: Pierre de Saulon (canon of the Duvale chapel, Guillaume

de Bressey, Hugues L’Orfevre) took active part in confiscating the 22 houses belonging to the Jews. All their belongings

were sold to auctions, and the 25 houses in Dijon among which were “the school, the Shabbat hall and the small house

in front of it, the house in front of the cemetery, and the house of Rabbi Drouin”.

A complete inventory and estimation of the furniture, money, debts, livestock, and vineyards was made together with

the land belonging to the Jews. The total revenue of the sale reached 3411francs. The duchess retained for herself the sum of

912 francs. Still there was the furniture to estimate, the wine, the wheat,

the cattle the vineyards, the jewellery etc. There were also the credentials found in the houses of two famous Jewish bankers in Burgundy. Those confiscations went as far as Salives and Baigneux (the only village that has retained in its actual

name the souvenir of the Jews: Baigneux-les -Juifs) What happened to the Jews who were expelled from the duchy

of Burgundy in 1306 ? A part retired in the county of Burgundy where some apparently obtained the duke’s tolerance and

enjoyed passing privileges. From 1311 to 1317, we find here and there, in Dijon

and Beneme, old people expulsed from 1306 as well as new names. In 1321, a new

expulsion this time by Philippe Le Long, took place in Burgundy, by a decree signed by Philippe V, as harsh if not more, than

the previous one. By 1360, Dijon became again as in the past a centre of trade

for the Jews of France like the one king Jean determined by law in 1361. The

Duke Philippe le Hardi gave the right by law to 12 Jewish families to live and to trade in the duchy for 12 years with guaranties

and privileges. Later, another 8 families were admitted in Dijon under the surveillance

of two delegates of “La Nation Juive”. The jewish community was flourishing

and in 1382,Guy de Corp, a notary registers some marriages. In 1394, the definite expulsion ordinance is signed by Charles VI. Three hundred years later, following the decree of 1791, banished

Jews reappear in Burgundy. Translation by Luna Cemachovic.

|

|

The Doctors of the Dukes followed by The Jews at the revolution

The

Jews upon leaving left behind a part of their own people who were tolerated and accepted for two reasons.

Some of them doctors were in possession of useful secrets. One of them

Salomon de Baûme, whose wife Marroine was banker of Dijon, while he treated patients,

stays until 1417 in the city where his treatments were considered a marvell to the point where a widow in Dijon gave him a pension of 10 francs between 1388 and 1391 in order to treat her. Others followed him of no lesser reputation. Abraham the Jew was

the doctor of Henri de Bourgogne count from 1310 to 1318. Master Benoît

the physicist, Master Perret who from Dijon came to live in

Besançon. Salomon de Baûme surpassed them all by his reputation

which often incited dukes and duchesses to employ him: with him, it was Master Elie Sabbat that Jean Sans Peur invited to

come to Paris in 1410 and to Brugges in 1411. Those two doctors became secret emissaries and especially Master Mousse, who led to Paris in 1410, the Jew Haquin de Vesoul who became the future doctor of the duke and stayed

with him until this prince’s assassination in Montereau in 1419.

Apart from the doctors the Jews left in Burgundy

a certain number of their own. We are talking about the baptised Jews: Joseph

of Vesoul will be calling himself Louis d’Harcourt. In August 1415, there is, in Beaune, a Jew Jean “the baptised

of Burgundy” who will be sent in order to translate

suspect letters addressed to Salomon de Baûme from his wife suspected to have poisoned water fountains. Jean, Jew from Besançon, is rector of the house of Citeaux of Fixin in 1306. “Simonet the

Jew” is notary in Dijon in 1335. Jews

at the revolution All the Jews that came to

live in Dijon after the revolution originate from Alsace.

Here are the names of the major families and the dates of their arrival: Caen(1790), Lévy, Blum, Samuel (1792), Brunschwig (1793), Houlmann,

Hess(1794), Picard, Crombak-Sivry (1795), Aron (1796), Joseph (Isaac) (1797), Lyon (Abraham) Israel, Créhange (1799),

Lièvre, Salomon (Isaac) (1800), Jacob (1802), Bernheim (1803), Sirque (1804).

There are also the families by the names of Cerf, David, Dougas, Fuld, Godchaux, Haas, Heiman, Henstein, Lazard, Mayer,

Nathan, Nordman, Polacre, Rheis, Schmoll, Worms, Weil which feature in the registries of 1808

and many of who have still descendants in Dijon.

The first synagogue of that period was Rue des Champs; today it is Rue des Godrans.

The three Jewish school-masters lived: Simon Cerf in rue du Chaignot, Abraham Lyon, rue Voltaire (now Berbisey), Joseph

Isaac, rue des Etioux. The synagogue being too small it is

transferred at la Maison Goisset (ramparts of the castle), then in 1829, in a part of the apartments of the Prince de Condé

at the lodging of the King (town hall) due to a lease passed in November 1829 according to which the Jews paid 480 francs

a year.

It was framed on the 1st August of the same year “regulation of order and by law of the Israelite

temple of Dijon.” Approved by the departmental consistory of Nancy. In 1841, the city handed over free of charge three halls on the ground floor of the

Town-Hall, with its entrance rue Porte-au-Lion, and des Forges. This synagogue

remained as such until 11 September 1879. On the 5th of April 1865,

a voluntary subscription opened among the Jews an later among the people of Dijon, a piece of land was asked from the city,

and after many ups and downs, a decision of the debate of the municipal Council gave to the Jewish community the necessary

piece of land on one condition: “Works should start before 1st of January 1871.” The advent of the war yet again thwarted these plans and the first stone was only set in 21st

of September 1873 (Rabbi Gerson).

Translation by Luna

Cemachovic

|

The terrible Years What was the situation of these communities just before the Second World War? In the absence of religious statistics in a secular nation, one could not risk any conclusions. The

community of Dijon was big enough to have a rabbi attatched. In September 1939, the rabbi Elie Cyper went to the army as army chaplain of the VIIth

region. As an evaded prisoner, he accomplished in Perigueux remarkable work. Arrested by the Gestapo on April the 8th , 1944 he was deported to Drancy on the 15th of May in a convoy consisting only of men in direction to Kaunas

in Lithuania where they were killed. Numerous Israelites living

in Burgundy before 1940 or refugees after the exodus suffered

the same fate as the rabbi Elie Cyper.

A unpublished report by André Meyer, professor in the Faculty of Sciences and president of the Cultual Association

of Dijon, dated July the 28th 1946, specifies: “An important part of the Jewish population of Dijon

came in Dijon after the armistice. It is only in 1941 and 1942 that the Jews that came back in Dijon

(approximately half of the Jewish population of 1939) took the route to the south zone and thanks to numerous connections

succeeded in their majority to cross the line of demarcation or the Swiss border. The

first arrests of foreign Jews started in July 1942 and incited everybody to run away from the German measures.” Many personalities from Dijon made these escapes easier: the canon Kir, Professor Connes. The canon Kir prevented the synagogue, which was entirely plundered and from where only the scrolls of

the Law were saved, to be destroyed by the Germans. He sheltered and took in

Jews in a Catholic support, furnished the fugitives with false papers and handed them over to ferrymen.

Despite the Red Cross assistance, the arrests of the Jews were as devastating in Dijon

as elsewhere. In December 26th 1942, 10 local Jews were taken as hostages. On July the 13th , it was the turn of 10 more, this time foreigners. In the end, following the issuing of general orders, in February the 24th

in 1944, by the SS Sturmbannfuhrer Hulf to proceed in his circumscription to the general clean-up of the Jews, all the Jews

of Dijon were arrested in February the 26th, transferred to Drancy on

March and then deported. From the 92 people arrested during this operation

in Dijon and its environs, only 2 came back from Auschwitz, which is in accordance with the

average proportion of repatriation for the “racially” deported of France. A note by professor Meyer gives an indication about the fate of the children put into

public social assistance. A 6 years old young girl in 1942 was taken to the U.G.I.F.

by Mrs Damesme with false papers in the name of Davy as well as her two 10 years old twin brothers in 1942. A brother and a sister, 16 and 14 years old respectively in 1942, trusted to the care of the U.G.I.F. were

found in 1945 living with the person who had taken them in. On the other hand

a 10 years old girl put in 1944 to the care of the French police disappeared. It does not lack interest, even if it may appear

tedious, to know the precision with which these arrests were performed. The clean-ups

took place in the big cities but no small city was spared either. In Joncy (district

of Charolles) the “movement of the administrative regrouping” of 1942 reached 19 foreign Jews. One may note arrests

made under particular circumstances. A police officer’s report in November 25th in 1945 by the chief of the

police force of Paray-le-Monial, after having given the names of 22 Jews, French or otherwise, arrested in 1942, contains

this note:” All these Israelites were arrested by the military of the Feldgendarmerie of Paray-le-Monyal, while trying

to cross the line of demarcation during customs control at the train station of Paray-le-Monial. They were in principle sent in the German prison of Autun. Before their departure, they were deprived of

all their belongings and jewellery. When delivered to the police force, the German

recommendation was to isolate them completely from the other civilians, under pain of punishment for the chief of the force. The treatment suffered at the Feldgendarmerie is not known.”One notes also that

Jews were arrested also beyond those more radical clean-ups. In Geugnon (Saône-et-Loire)

the Gestapo took hold of two Jewish women, one of Polish and the other of Alsacian origin in April 13 in 1942. In Semur-en-Brionais,

in Marcigny, in Louhans, Autun, Creusot, at Sennecey-le-Grand, at Dompierre-les-Ormes, in Tramayes, at Saint-Gengoux-le-National

in particular, we note in the department of Saône-et-Loire, arrests taking place under the orders of the Vichy administration. Those arrests do not all

coincide with the round-ups of September or October 1942 under the orders of the Germans. Mrs Cahen was “under

supervision by the chief of the prison in Auxerre and probably died there a couple of days afterwards.” If at Tonnerre and its surroundings one does not note arrests concomitant with the operations which took

place in September 1942, one still learns about two arrests in Seignelay, in February 1944, as ordered by a circular of the

chief of the police, and one arrest in Courson at the same day under the same circumstances.

They were the consequence of orders by Hulf. At Saint-Valérien,

in the hamlet of Petit-Paris, a family of three people was arrested in 24th of February 1944. On the same day at Villeneuve-l’Archevêque, it was the turn of the Javal family. A report by the chief of the police mentions that “Mrs and Miss Javal, from the domaine of Vauluisant,

parish of Courgenay(Yonne), were the object of a police statement n° 57 and

58 dated 24.2.1944 and under arrest. Mr Javal, who should have been also arrested

since he was mentioned in the same prefectorial requisition was not arrested

in the end because of his impotence. On the 11th of March 1944, the

latter was arrested by the Germans, who after having sealed his house, took him to the hospital of Sens but any trace of this

man has since completely disappeared.”

On the same day, Mr. Etlin, 46 years old, and Miss Levy, 58 years old,

both of French nationality, were arrested by the police in Sergines to be transferred in

Drancy. At

Charny, at Villeneuve-sur-Yonne, at St-Julien-du-Sault, the some few French Jews that lived there were arrested on the 25th

or the 26th February 1944. The only ones that came back were the Schwartz

brothers who were not deported since they were considered half Jews since born to half Jew parents. The records from the department of Nièvre mention similar facts.

Under the orders of the Sicherheitspolizei of Dijon, transmitted by regional police management, the order to arrest

the French Jews, is put to execution in Cosne in February the 25th in 1944 and in Decize. Their foreign coreligionists had already been “reassembled” since autumn 1942. At Sens, after

the clean-ups of strangers in July and October 1942, 4 French Jews were, according to the chief of police “arrested

following a German decision of that period, and the only motive of their arrest was because they were Israelites.”

Translation by Luna Cemachovic

|

|

SAMUEL BLUM, membre

influent de la communauté israélite de Dijon Connaissiez-vous l’histoire du train touristique qui emprunte 7 km de

la vallée de l’Ouche dans un site superbe que l’on appelle maintenant la Suisse bourguignonne ? Vous

roulerez sur ce qui reste d’une extraordinaire aventure ferroviaire d’un membre de la communauté israélite

de Dijon. Nous sommes au début du XIX ème siècle.

La fabrication de la fonte et de l’acier exige des moyens de transport pour rapprocher le minerai de fer de celui du

charbon. Alors, un de ces hommes entreprenants qui vont faire

entrer la France dans l’ère industrielle va transformer la région, il s’appelle Samuel BLUM

(cité plusieurs fois dans le volume 2 Histoire de Juifs Bourguignons de Henri-Claude Bloch). Il obtient

en 1826 la concession des mines de houille d’EPINAC . Il lui faut alors acheminer ce minerai jusqu’au canal de

Bourgogne dont la construction s’achève et qui n’est situé qu’à 27 kms. Cet homme s’inspire de ce qui existe déjà en Angleterre mais

aussi en France sur une ligne de chemin de fer toute récente qui permet d’acheminer le charbon de la région

de St Etienne jusqu’au Rhône . C’est ainsi

que le Roi CHARLES X, après avoir déjà autorisé en 3 fois la construction de cette première

ligne française jusqu’à Lyon , va autoriser le 7 avril 1830 la construction de la ligne entre EPINAC et

Pont d’Ouche, là où le Canal de Bourgogne va passer au plus près. Vous êtes donc sur la

deuxième ligne ferroviaire française mais c’est aussi la première fois et l’une des seules

que , tenez-vous bien, que tout se fera par expropriations alors que cette voie ne sert que des intérêts

privés. C’était déjà exceptionnel

à l’époque, ce serait impensable aujourd’hui. Mais les pionniers ne sont-ils pas ceux qui précèdent

les lois ? Samuel BLUM va évidemment devoir faire

face à l’opposition des propriétaires locaux. Pourtant, il va, comme l’on dit maintenant ,

se les mettre très vite dans la poche. Eh OUI ! La ligne descend légèrement ; La

voie est étrange, on en voit encore un morceau reconstitué au musée de Mulhouse. Les rails sont en effet

posés, non sur des traverses mais sur des plots en pierre. Pourquoi ? simplement parce-qu’il n’y a

pas encore de locomotives et les wagons remontent à vide tirés par des bêtes qui marchent entre les rails. Ces bêtes ? Elles appartiennent aux cultivateurs riverains qui vont

profiter du train minier et regretter l’apparition des premières locomotives en 1855. De cette époque que reste-t-il ? regardez bien. Côté montagne à

gauche en descendant et à droite en montant, nous découvrons, quand la végétation ne les a pas

envahis, de superbes caniveaux ou escaliers en pierre taillée protégeant la voie des eaux de ruissellement.

C’était avant l’invention du béton et l’utilisation des caniveaux pour y faire passer des

câbles. Avis aux volontaires, nous avons des pelles, des pioches et des serpes pour tous ceux qui voudront nous aider

à restaurer ce patrimoine de bel ouvrage. L’écoulement

du charbon va ainsi passer de 5.000 tonnes en 1830 à 160.000 tonnes en 1860. De ce trafic, il reste des vestiges dans le sol surtout vers le terminus, là où l’on

se souvient encore avoir vu certains ramasser des morceaux de charbon pour se chauffer. La compagnie du PLM atteint Epinac et permet d’éviter le chargement sur le canal. Notre

ligne perd peu à peu le charbon. Est-ce la fin ? Non, car la population en a assez de voir des trains passer sans

pouvoir les prendre. Les pressions sont telles que le PLM va céder, racheter la voie et, non seulement ouvrir le train

aux voyageurs en construisant de jolies gares, mais surtout prolonger la ligne jusqu’à Dijon. Cela se réalise

enfin en…1905. Une nouvelle ère s’ouvre, celle d’un chemin de fer rural avec 2 clients marquants :

la cimenterie de Crugey et la plâtrerie d’Ivry.. Mais cette ère durera peu. Lors de la seconde guerre mondiale,

le trafic est si faible que l’armée allemande envoie sur le front de l’Est les rails des 15 premiers kms

de la ligne initiale. Après la

libération, la ligne vivote. Les Dijonnais disent qu’elle dessert les « Trous sur Ouche ».

Pourtant un train est célèbre, celui des pêcheurs.

Il ne roule que les dimanches. La SNCF, bienveillante, le laisse partir de Dijon très tôt. Il s’arrête

à la demande le long de l’Ouche et du canal. Il repart le soir de Bligny sur Ouche et reprend les pêcheurs

avec…tous les poissons pêchés bien sûr. En

1968, la SNCF vend tout, rails, maisonnettes et terrains jusqu’à Dijon . Le SIVOM du canton de Bligny sur Ouche

et la commune de Bligny achètent respectivement les 7 kms d’emprise de voie dans la haute vallée

ainsi que la gare de Bligny elle-même. Est-ce encore la fin de cette ligne historique ? Aujourd’hui, le chemin

de fer de la Vallée de l’Ouche est une association composée entièrement de bénévoles.

Une bonne idée d’excursion pour un dimanche de printemps sur les traces de Samuel Blum. http://cfvo.blogspot.com/ JCM Une partie des informations ci-dessus

ont été transmises par M. Jean Yves Tuffery – Maire de Colombier et Président du CFVO.

|

Courrier

du Rabbin Cyper de Dijon en 1939

|

|

|